Industry Transformation: Enablement, Disruption and Competitive Dynamics Along the Value Chain

Rick Zullo, Co-Founder & GP @ Equal Ventures

At Equal Ventures, we are laser focused on helping founders transform legacy industries. While many founders and firms speak about “disruption”, we feel transformation is a far more ambitious and holistic goal that better reflects the opportunity set for founders today. By definition, “disruption” implies the economic destruction of the existing value chain1. For various reasons, this is incredibly rare, and more likely resembles a gradual take over. With that, however, we see a lot of founders focused on “disruption” without thinking through the potential for “enablement” or the overall impacts on the broader value chain.

The reality is that these two concepts are intrinsically linked. If you are an “enabler” for certain stakeholders in an industry, you’re likely “disrupting” others. Industry value chains are an interconnected web of stakeholders, reflecting the steady-state economics (“profit pools”) and competitive dynamics of those stakeholders. “Transforming” an industry represents the opportunity to shift that steady-state value-chain, resulting in changes to the competitive dynamics and economic rents of those stakeholders along the value chain. The word “along” is incredibly important here, because if a company is truly successful in its intention, impacts will reverberate across all of its stakeholders (not just a single sub-set).

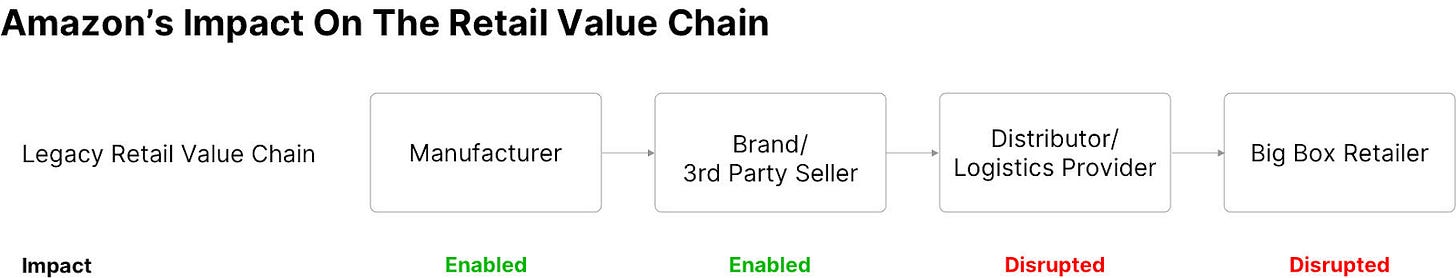

Perhaps the best example of this is Amazon. Amazon has transformed the existing retail landscape like no play ever has. Big box retailers have been disrupted, unable to compete with Amazon’s cost, selection and convenience. Amazon, however, enabled countless small businesses (via its 3rd party marketplace and Fulfillment by Amazon offerings) who would otherwise find it economically unproductive to reach customers. We’ve seen countless examples of Amazon entrepreneurs. These impacts have not only been felt in retail, but the adjacent industries supporting retail like logistics. Trucking, warehousing, shipping, delivery – all of these industry sub-segments have been forever changed by Amazon. This example isn’t intended to glorify Amazon, but rather to illustrate that value chains are interlinked, making an understanding of the competitive landscape critical to understanding how your company will enter and transform an industry.

All too often, we hear about founders “disrupting an antiquated industry”, but in reality that is VERY rarely the case. There are cases where they may be disrupting individual segments of that industry, but rarely is the entire value chain at risk. More often than not, these players enable more than they disrupt. In reality, this is often a necessary condition for survival in the value chain, relying on collaborative ties to the industry’s stakeholders (whether as customers or partners) to achieve relevancy. Our team will often look across the value chain, determine the cost structure of various different segments and take a forward-looking view to ask “if successful, how will this company impact the economics of other stakeholders?” When we find a company that significantly improves the efficiency and economics of the overall value chain (often by enabling some and disrupting others) we know there is an opportunity for something special2.

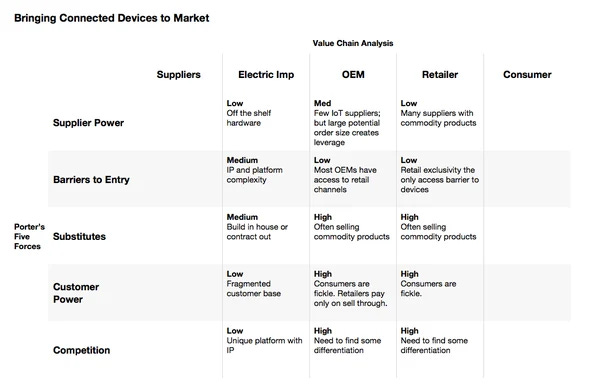

Ultimately, we believe industry value chains are fundamentally different than IT value chains. As asset-based industries turn over to digital solutions, the power dynamics can shift quickly. Incumbents know they have a LOT to lose. I’ve seen this with companies like Workrise (fka RigUp) and we are quickly seeing it occur with others in our portfolio. For industry transformation to occur, a great product that sells simply isn’t enough, as companies may develop a false sense of product market fit before seeing competitors and incumbents swoop in. This is why it’s important for founders to consider the relative strengths of various segments in a value chain to determine how willing existing stakeholders will be to engage and/or compete with them and how. Ultimately, the strength (or weakness) of those players should inform who you choose to disrupt and who you enable. We find Tomasz Tunguz’s post on the “grand unifying framework” (see below) to be a helpful tool for evaluating these competitive dynamics.

Industry transformation is never easy, but it represents perhaps one of the most meaningful economic and social opportunities of our time. We developed Equal to help founders seize this opportunity in the sectors/industries that we think are ripe for that transformation and encourage founders to consider the competitive dynamics of their value chain (and their decision on who to disrupt and/or enable) as a core component of their mission, strategy and OKRs.

If you found this post helpful, please share and if you are a founder looking to transform any of our industries of interest, please reach out!

Schumpeter (an early influencer to Carlota Perez and Clayton Christensen) first brought this concept forward in the 1940’s-50s through the concept of “creative destruction”.

For those looking for further reading on this exercise, I’d recommend The Value Imperative by McTaggart, Kontes and Makins